Understanding Why the Iranian Protest Movement Stalled: Parts II & III

The wrong organizational model & ignoring insider strategies

#2: The wrong organizational model and culture

The first essay of this series explored the lack of a strategic orientation among those seeking a more democratic Iran. The democratic movement must recognize that political struggle is not simply the expression of your identity or beliefs – but rather an instrumental question of choosing tactics which maximize power. A deeply related issue is the structures within which we can organize for power.

Unless you are a billionaire oligarch, the main context within which you can ‘do politics’ is through collective organizations. If your perception of political work is simply the expression of your individual preferences, then you are bringing a knife to a gun fight. Individuals operating as individuals are not the relevant agents in political life – but individuals operating through organizations.

This may not be self-evident in parliamentary systems with complex background infrastructure which allow hundreds of political conflicts to be narrowed into ticking a ballot for the blue or red party every four years. Nonetheless, these countries have serious distributional and political conflicts occurring behind the scenes between organized groups and powerful individuals.

Admittedly, the poor and working majority in the global north has been disenfranchised from this “organized conflict of interests” – and instead slumped into practicing politics purely as self-expression of beliefs and identity.

But however difficult, there is no way to contest power, especially in a non-parliamentary or non-constitutional manner, without collective organizations. Modern politics is how society organizes itself at scale; therefore requiring corresponding organizational forms which are organized at scale.

Unfortunately for the Shah and fortunately for the Islamic Republic, the organizational form of political participation is very different in the 1970s and 2020s. In the previous era, doing politics looked like forming a democratic-centralist group with like-minded individuals. Today, doing politics looks like posting an Instagram story (or if you are really committed, forming your own Telegram group).

Today’s social media-based approach is deeply ineffective. It is not particularly difficult for governments to monitor the social media activities of dissidents. Therefore, those choosing social media as their main vector of struggle are only safe to the extent they are ineffective.1

In contrast, the older type of organization common in the 1970s had high barriers to entry and exit, generated a high frequency of repeating interactions between members, had clear visible hierarchies, and was overall better-suited for collective action.

High barriers to entry and exit means that individuals could not costlessly join or leave the group. Introducing some ‘friction’ to entry and exit makes organizations less malleable but more resilient. Prospective members had to be sufficiently ideologically aligned with a group, thereby ensuring coherency. This common alignment would also often be emphasized in an onboarding process. Barriers to entry also served as a filter to keep out grifters and other problematic individuals.

High frequency of repeating interactions, across different domains of activities like reading groups, social events, and protests, ensured cooperation and built a common culture and identity. Ensuring and facilitating repeating interactions between members deepens their bonds and collective trust; thereby making the organization more effective.

Consider the difference between how you treat political differences between your lifelong friends and Twitter mutuals. Deep ideological differences with friends are less likely to challenge the existence of such friendships, because these relationships cross multiple domains. But slight and miniscule ideological differences among individuals whose only affinity is ideology (like Twitter mutuals) are existential. Organizations (especially democratic-centralist ones) can transform relationships that are initially only ideological (and therefore at risk of disintegrating due to minor differences) into something more like friendship.

This process results in the development of an ‘in-group’ sensibility whereby members are more trusting of each other’s underlying intentions. This tolerance of difference will in turn actually reduce differences in opinion over time, as members worldviews develop through debate, reading, and common inputs.

Repeating interactions also builds predictability, which is a prerequisite for communal organizing. You cannot rely on others, especially at scale, without having a strong predictive sense of what they will or won’t do. Building rapport and predictability allows for mutually complementary approaches between members.

The development of internal cohesiveness and community further snowballs, as the group’s material interests can also converge over time.

Democratic-centralist organizational forms also provide clear hierarchies. Anyone with experience in ‘horizontalist’ or non-hierarchical political groups can testify to their sheer ineffectiveness. Those with social skills that have participated in such groups will also have experienced how relatively easy they are to game and manage for the benefit of certain cliques.

Hierarchy will always exist in organizations. People differ in the ability, interest, and availability when committing to an organization – thereby always implicitly producing a hierarchy. Being open and structured about such hierarchies generates accountability, coherence, and organizational effectiveness. Some of the few in the diaspora and Iran that have attempted to form new organizations have fallen into the horizontalist trap. This approach to organizational form was a cancer that crippled the post-2008 democratic movement in the global north – and risks doing the same to Iran’s democratic movement.

Lastly, democratic-centralist organization forms, for all the reasons listed above, are much better at maintaining the security and anonymity of members. The IRI’s current leadership is mostly fine with the millions who post opposition messages on social media – but organizing a local reading group will likely result in a run-in with the local intelligence office. In this context, it is imperative that individuals struggle within structures that facilitate a security culture.

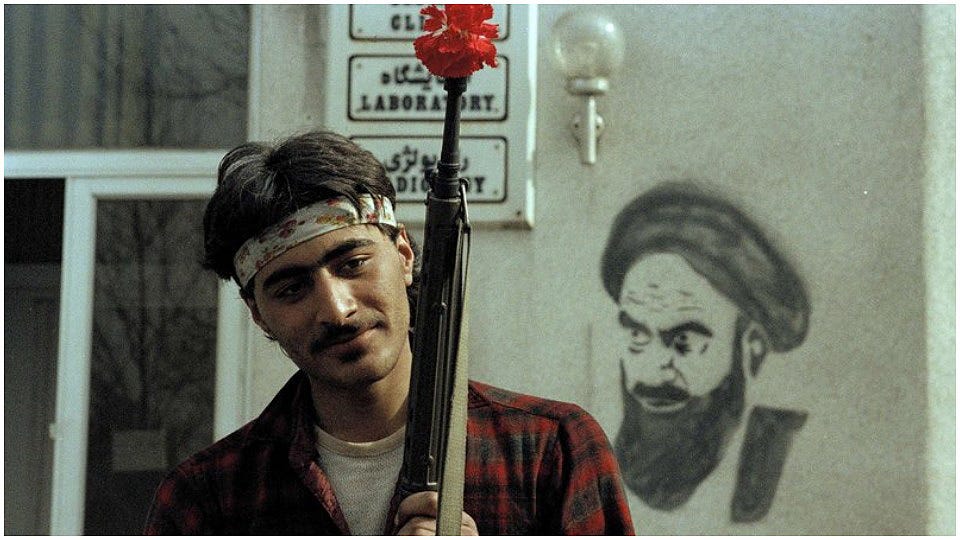

The purpose of this post is not to necessarily promote the ideological substance of the democratic-centralist groups of the 1970s – but rather to highlight their organizational form (which succeeded). Iranians are blessed with the living memory of a successful revolution; no other tool is as powerful when attempting to conjure new emancipatory forces.

#3: Misplaying insider versus outsider strategies

The previous essay emphasizes the necessity of collective organizations. But in today’s Islamic Republic, forming such organizations can be challenging or impossible. In turn, this essay explores the political options available to individuals inside Iran.

One way of understanding political life in Iran is that individuals can participate as insiders or outsiders. Being an insider means operating within a certain perimeter and being considered safe, in-group, or khodii by those within the power structure. Being an outsider means operating ideologically unencumbered but outside the perimeter of acceptable political contestation – and thereby incurring the hostility of the security services.

There are tradeoffs between the two approaches – and sometimes the choice is made for you. But an insider strategy can be highly effective, even in today’s Islamic Republic. Insider strategies are not limited to high politics, but also include participating in and building other types of power – including cultural, financial, and social. Operating businesses, organizing charities and foundations, operating media, or working in academia can all be insider strategies. Being an insider in the IRI today does not require a particularly Faustian bargain. Tens of millions of Iranians participate in the country’s political life, often proximate to centers of power. The Islamic Republic does not require those considered in-group to burn down a Baha’i temple every week to prove their loyalty. Being considered ‘safe’ from the IRI’s perspective is contingent on questions of tact, signaling, and symbolism – not meaningful ideological exams.

The porousness of the IRI’s political life is reflected not only by its top-down infiltration by foreign intelligence agencies but by those common anecdotes about so-and-so’s cousin in the IRGC who is opposed to the Islamic Republic, etc.

Within the perimeter of the IRI, there remains substantial room for political disagreement. You may not be able to openly challenge the system of Supreme Leadership, but you can advocate for independent labor unions, fairer elections, women’s rights, etc. As the experience of the edalatkhah movement demonstrates, even labor organizing, usually a third rail for the IRI, can be conducted in an insider manner.

Most importantly, Iran is a capitalist country. This means that a great proportion of social and economic organization is organized through the ‘private’ sector, and therefore not as subject to the IRI’s ideological perimeters. The capitalist nature of the Islamic Republic remains its Achilles heel, as it leaves some breathing room for Iran’s nationalist-secular elites. Simultaneously, it generates fragmentation and intra-elite competition within the Islamist elite.

Below the Olympian heights of the Leader, President, and other senior leadership, most power in the IRI is exercised by a middle layer of security service officers, cultural workers, bureaucrats, and managers. The overwhelming supermajority of this layer is opposed to the status quo – though that opposition can be expressed in different ways. A majority of this layer is hostile to the current Raisi administration. A substantial proportion’s hostility extends further to the entire ruling clique, and a smaller but still substantial minority is opposed to the entire constitutional order. This includes individuals who own some of the largest businesses in the country, run schools, large institutions, hospitals, etc. Iran has open a wide and fertile terrain for elite political contestation. Totally abandoning the field, and ensuring the victory of the current clique’s purge, would be a mistake for Iran’s democratic movement. Abandoning power inside Iran, even if it is ‘private,’ in order to wave a Pahlavi or Pride flag in Toronto every few months is undoubtedly a strategic error.

Sadly, the Iranian opposition has stumbled blindly into an approach that is optimal from the IRI’s perspective. Anti-IRI Iranians have voluntarily outed themselves as outsiders, thereby closing off any real participation in public life, whether through elite or popular politics. At the same time, they have adopted outsider strategies, like hijab non-compliance, which are fairly low-cost for the IRI. Not only has the opposition failed to identify the complementarity between insider and outsider strategies, but much of its energy is spent attacking those pursuing insider strategies.

This is an ideal outcome for the IRI’s current leadership. Its most qualified rivals are removing themselves from political life and, once removed, are not choosing outsider tactics (like armed struggle) which would impose high costs on the IRI. Instead, the Islamic Republic’s ruling clique can rest easy knowing that all problematic individuals are self-purging from any position of power in order to mostly post on social media.

If you are unwilling to incur the cost of building underground parties, then the insider strategy is the best alternative. If proximate to the elite, it allows for meaningful political contestation as an individual – and even allows for some organization-building (though the latter is much more carefully monitored by the IRI).

Choosing insider versus outsider strategies should not be considered abstractly in a vacuum. It is highly contingent on the context. With the benefit of hindsight, we can probably say that the Tudeh Party erred in committing to an insider strategy for too long in the early years of the IRI. Perhaps, its adoption of a hard-outsider strategy, along with other leftist groups, could have shifted the Islamic Republic’s trajectory. Conversely, Ayatollah Montazeri gained nothing and lost everything by adopting an outsider strategy just a few months before Khomeini’s death. In fact, the 1988 executions are illustrative of the IRI’s best weapon against insider subterfuge. Ervand Abrahamian writes that the executions were intended, not necessarily to purge the outsider-leftist threat, but to impose a high ideological loyalty threshold that would weed out the progressive-insider threat through self-purging. Power has a difficult moral calculus – but the high moral cost of Montazeri and his supporters remaining insiders after 1988 would likely be offset by democratic opening it could have provided.

Admittedly, the strategies in this and the preceding essay are in tension, though not completely in opposition. There is complementarity between insiders and outsiders seeking democratic outcomes. Through radical flank effects, outsider strategies can empower insiders. Conversely, insiders can mitigate the suppression faced by outsiders.

In the short-run, a reasonable approach would be for diaspora Iranians to take on the burden of building outsider organizations, as they are not substantially at risk of suppression by reactionaries within the IRI.

In other words, there is no arbitrage here. If posting is 90% safer than in-person organizing - it is then exactly 90% less effective. It is not a situation where online activism is 90% safer but only 80% less effective.